General

Perhaps the most significant element of the car is its paintwork. For a vintage car, besides the quality of the paint job, the correct historically chosen shade is essential.

The issue of color usually arises during the car’s restoration, when we want to determine the color the car originally left the factory with, or when choosing a new color from the collection of original shades. Sometimes it’s just about confirming whether our car still has its original paint – for example, experts told me that my Octavia could not possibly have its original paint because the blue 407 was supposedly never used on that model. The truth can be found using the engine number in the Škoda Museum in Mladá Boleslav (Muzeum Mladá Boleslav) in the Vehicle Record Book, which lists the date of dispatch, place or buyer, body and upholstery color. Based on the original color charts, we can then verify the actual color. That’s how I found out my car was produced in an exceptional, non-standard shade. Back then, exceptions were quite common – mostly due to the general shortage of materials.

Once we have identified the color number and its true shade, the next challenge is converting it into modern color codes like RAL, STANDOX, GLAZURIT, PPG, etc.

How to select and identify shades: version 1

1. By using an original piece of the bodywork – you can compare it (trial and error) to find a matching modern product (spray/paint can).

(That’s how I proceeded with my Spartak, where the original was “Beige 11”, and I finally matched it with 2-24 Motip spray.)

2. By converting from the color chart of the Škoda Museum in Mladá Boleslav into the newer “Barvy a Laky” series, particularly the “Škoda” range. Many shades were produced well into the 1970s–1980s.

(That’s how I proceeded with my Octavia – from “407” to the newer “4550 – Signal Blue”. Unfortunately, it’s not available in spray, only in a can.)

Mixing paint into a spray didn’t go well for me – they couldn’t match the right shade according to their RAL series, and the paint didn’t cure properly because “they can’t add too much hardener, otherwise it would dry inside the spray can and wouldn’t spray!”. So, if it’s available in a can, it’s better to use a spray gun...

How to select and identify shades: version 2

1. By using a metal sample with original paint directly at the paint shop, comparing it with their color charts, just like with a modern car without a color code.

However, there are often issues:

a) The car has its original color, but it’s faded, and even from hidden parts of the body, you can’t be sure of its original appearance. Or you simply want to be certain before investing 200,000 CZK in a full restoration.

b) The car has already been repainted in the original shade, but you don’t want to repeat the same dull color that was common back then (as in our case with the blue 1201 STW). You’d prefer a more interesting or cheerful (yet still original) color.

c) The car’s condition makes it impossible to tell anything original, and you face the choice again.

In such cases, you need to bring a color chart to the paint shop and proceed according to step 2:

2. Using color charts

The paint shop will mix or match the paint based on their modern charts.

Sometimes, even without a physical chart, a paint shop can identify the shade just from the number or name. For example, “8850 Jawa” – many paint shops know such shades from Jawa motorcycle restorations or from older Škoda models that used these tones (mostly those that continued into the Škoda 100, 120, or Favorit era).

a) Period “AZNP” color charts (originals or high-quality copies). I discovered, for example, that the widely seen greenish “Beige Olive” spray was actually incorrect, and only by researching in the Barvy a Laky archives did I find the true beige-olive sample (a spray-on paper), which I borrowed and compared with modern converters to find the correct RAL equivalent.

b) Later “BaL” four-digit charts (originals or good copies) – the second column in the table. Only some older Škoda shades survived into the 1970s–1980s, so these charts are still possible to find.

The original paint composition of Škoda cars consisted of: “multi-layer” = base coat + fillers + baked synthetic enamel.

History of color coding

Color coding system for 1950s cars: unclear, with various numbers such as 11 or 407 – it seems there was no unified system.

Color coding system for 1960s cars = 4-digit numbers

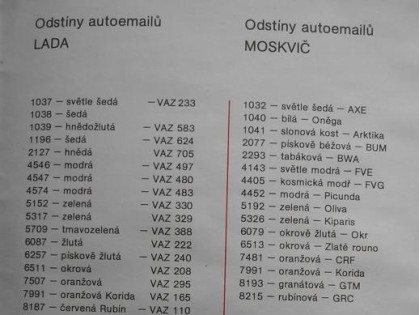

During the era of the national enterprise Barvy a Laky (“Paints and Varnishes”), which included nearly all paint producers in Czechoslovakia, new color shades from domestic manufacturers were assigned centralized 4-digit codes.

The numbering followed a basic rule dividing all color tones into groups:

- 1000–1999 – white, gray to black

- 2000–2999 – brown

- 3000–3999 – purple

- 4000–4999 – blue

- 5000–5999 – green

- 6000–6999 – yellow

- 7000–7999 – orange

- 8000–8999 – red

- 9000–9999 – others (aluminum, metallic, hammered finishes, etc.)

A specific four-digit code (e.g., 6050 Light Cream) ensured the same color tone regardless of which manufacturer produced it.

After privatization and the independence of Czech paint manufacturers: the central 4-digit system survived, but each producer now often has slightly different hues. Over time, cans and sprays began showing internal numbering systems, incomprehensible to the general public.

Parallel to this, global systems like RAL, STANDOX, GLASURIT, and PPG emerged.

In practice, no direct converter exists between these systems. In the section “Color Converters,” I include some conversions from the earliest designations to the newer 4-digit ones (e.g., 11 ? 6115), and sometimes even to current international RAL codes.

For interest – spare part numbering worked similarly

Spare part numbering system for 1950s cars (Spartak, Octavia, 1200...): unclear (various number lengths and formats)

Spare part numbering system for 1960s–1980s cars: OČM number (“Obchodní Číslo Mototechny” – Commercial Number of Mototechna), created centrally for all vehicles including trucks and buses, using a six-digit format: 111222333

- 111–vehicle type e.g. 110 = Škoda 1000 MB, 336 = Tatra 148, 341 = Tatra 815

- 222–assembly e.g. 420 = front axle

- 333–component detail

There were also additional rules – for example, if the 4th or 5th digit was “9”, it indicated accessories, etc. This nine-digit system began with the Škoda 1000 MB and lasted up to the Škoda Favorit (coded 115...). It eventually disappeared, as it was suited to the centrally planned socialist economy. Its advantage was efficiency: a single spring, for example, could appear under the same “Mototechna” number in multiple catalogs for different vehicles – and physically be identical.

Toward the end of socialism and afterward: alongside the OČM number, 12-digit codes JKPOV (“Jednotná Klasifikace Podle Oborů Výroby” – Unified Classification by Production Branches) began appearing.

In the 1990s: each manufacturer introduced its own numbering system. The older ones gradually faded out. Interestingly, even today, companies like PRAGOS – dealing in Karosa spare parts – still maintain databases containing all three numbering systems.